OPINIONS

OPINIONS

*Nicholas Ioannides (PhD)

Introduction

The Law of the Sea is an important branch of International Law which has developed rapidly in recent decades. The main reason that led to this development is the technological progress that enables states to exercise greater control over maritime areas, with the main purpose of exploiting marine natural resources (living and non-living).

The main text governing maritime affairs is the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (“UNCLOS”), which was the culmination of the Third UN Conference that lasted nine years (1973-1982). It is considered the “constitution of the oceans” and most of its substantive provisions are part of customary international law, which means that they are binding on non- States Parties as well. However, the UNCLOS is not the only conventional text on maritime law.

Also read: Nicholas Ioannides (PhD) | International Law and analysis of developments

In 1958, four conventions were concluded in Geneva (on the territorial sea and contiguous zone, the high seas, fishing on the high seas, and the continental shelf, while there was an optional dispute settlement protocol), which are still in force, although the UNCLOS has, to a great extent, superseded them. This article will focus on maritime zones and the delimitation process in order to clarify key concepts used in public discourse.

The status of the maritime zones

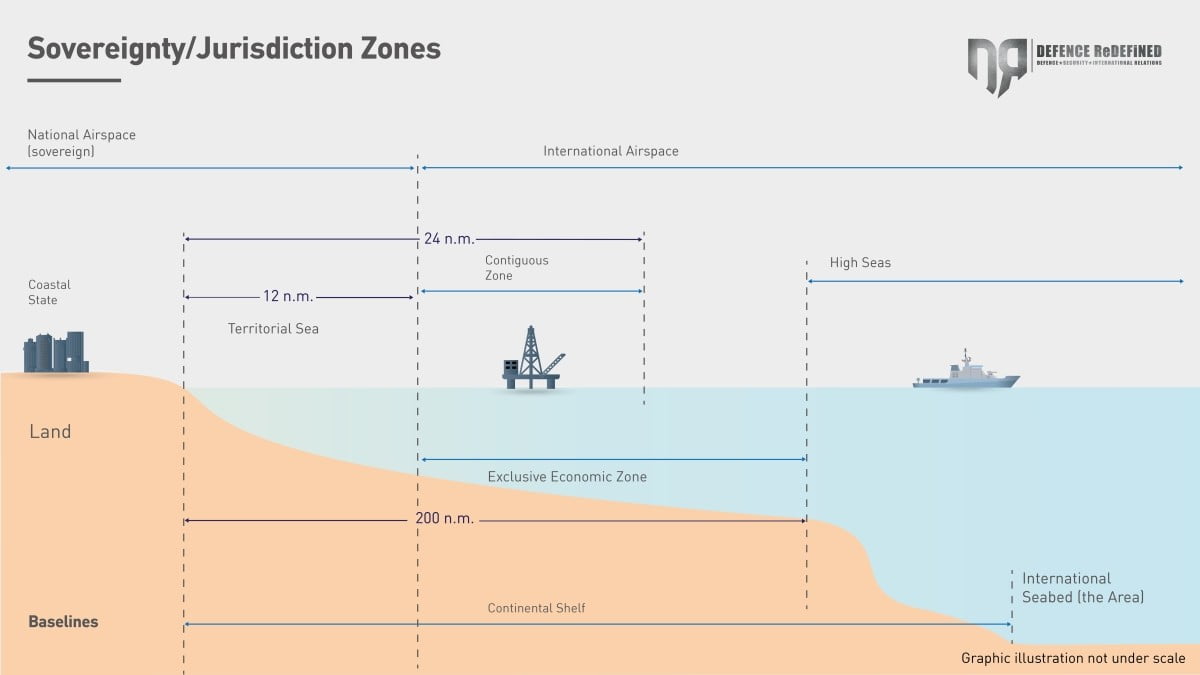

Initially, it should be noted that the maritime zones where states can exercise sovereignty/sovereign rights/jurisdiction are the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zone (“EEZ”). Beyond these zones there is the international seabed (the Area) and the high seas. The starting point for measuring maritime zones is the baselines that will either follow the natural coastline or, where the coastline is deeply indented and cut into, it will be, exceptionally, straight. The waters located between the baselines and the land are called “internal” (e.g. ports, lakes) and there the coastal state enjoys sovereignty.

The territorial sea is an inherent feature of state sovereignty, thus it does not need to be declared, and can extend up to 12 nautical miles (“n.m.” – 1 nm = 1852 meters) from the baselines, without excluding a lesser width (e.g. Hellas has 6 n.m.). In this zone the coastal state has sovereignty, while the regime of innocent passage allows foreign vessels to sail through the territorial sea without permission from the coastal state, as long as the passage is expeditious and does not endanger the security of the coastal state.

Also read: Legal analysis of the Exclusive Economic Zone delimitation Agreement between Greece and Egypt

The contiguous zone should be declared and may reach up to 24 n.m. from the baselines. However, the coastal state has no sovereign rights/jurisdiction in this area. It only has control rights in order to prevent and/or punish the infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations. There is also the possibility of declaring an archeological zone 24 n.m. wide, where the coastal state can exercise jurisdiction over the archeological items found therein.

The continental shelf, like the territorial sea, belongs ipso facto et ab initio to the coastal state and thus does not need to be declared. According to the classic definition, the continental shelf is the geological extension of the land beneath the sea. The UNCLOS also introduced a legal definition, which provides that all states have a continental shelf up to 200 n.m. even if they do not have a geological extension (this practice is called “legal fiction”). If, however, the terrestrial land actually extends underwater, then the width of the continental shelf can reach up to 350 n.m.

The coastal state has exclusive sovereign rights over the natural resources of the continental shelf and no other state may exercise them without the former’s permission. However, it should be emphasized that sovereign rights are of a functional nature (serving the economic interests of the state) thus bearing less weight than sovereignty, which allows the state to exercise the full range of its responsibilities.

The EEZ is also a zone to be declared by virtue of law or by concluding a delimitation agreement and in which the coastal state enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the exploitation of natural resources (living and non-living), but also with respect to energy production from the waves/underwater currents/wind. The EEZ includes both the continental shelf and the superjacent water column. However, the EEZ has not absorbed the continental shelf and thus they remain two distinct zones.

Maritime delimitations

In order for states to be able to exercise the above rights without hindrance, the maximum point to which they are entitled to exercise jurisdiction must be precisely determined. Therefore, in the event that two or more states claim part of the same maritime area, they will either have to enter into a delimitation agreement or have recourse to an international dispute settlement mechanism, which will be in charge of designating the maritime boundary between the parties. It is noted that in case of overlapping claims/rights, if there is no delimitation, then the limit that each state claims for its maritime zones cannot be final. The methods/principles of delimitation are two: a) median line/equidistance (the two states share the relevant maritime area equally) and b) equitable principles (all circumstances are taken into account and may not lead to a median line).

From 2009 onwards, international tribunals in delimitation cases use the “three-stage” approach: 1) drawing a provisional median line/equal distance line 2) examining relevant circumstances that may justify a modification of the provisionally drawn median line/equidistance line 3) ensuring that the result after the second stage is not disproportionate.

Concluding remarks

It is understood that the law of the sea is quite important for the international community and in particular for coastal and island states. Hence, if these states want to come up with a serious maritime policy, they should adhere to the relevant rules. In general, we should keep in mind that the coastal state has sovereignty only in the territorial sea. In the continental shelf and the EEZ it enjoys only functional sovereign rights/jurisdiction, while control rights apply in the contiguous zone.

The territorial sea and the continental shelf exist by right, while a contiguous zone and an EEZ need to be declared. Moreover, in order for the outer limit of a maritime zone to be considered final and opposable to third parties, a delimitation agreement or delimitation following a court decision must first be reached. During the delimitation process the methods of the median line/equidistance and equitable principles are being used, while the international courts implement the “three-stage” approach.

*Public International Law expert (University of Bristol)

Also read: US rejects Turkish actions in areas with potential Greek jurisdiction, Greek sources say

NEWSLETTER SUBSCRIPTION

A reluctant alliance? A different approach to French – Serbian defence relations

It has only been a few months since Croatia started receiving the first of the Rafale fighter jets it ordered from France.

The role of SERIOUS GAMES in the development of skills on Defense Standards

In an increasingly complex world, one vital factor for any successful organization is continuous capability building.

Strategy for Building Up Interoperable Defence Capabilities

Based on the current and emerging security threats and challenges in the geostrategic landscape, there is a…

USA | The leader of the Islamic State was killed in an airstrike in Syria

The US military announced midday Friday that it had killed ISIS leader Abu Yusuf in an airstrike in Deir ez-Zor province.

THEON INTERNATIONAL | German parliament approves the exercise of the 3rd option of the OCCAR Night Vision contract

Theon International Plc (THEON) announces that the Defence and Budget Committees of the German Parliament approved yesterday a new…

BATTLEFIELD ReDEFiNED 2024 | The premier Defence and Security Conference Successfully Concludes in Cyprus – Photos

The International Defence and Security Conference “BATTLEFIELD ReDEFiNED 2024” was successfully concluded on Friday, 13, December 2024…

Dark Eagle | Successful Test of Hypersonic Missile by the US Army

The US Army has successfully conducted a test launch of its new hypersonic missile system, “Dark Eagle,” after two years of delays.

GCAP | Industry Partners Reached a Landmark Agreement to Deliver Next-Gen Combat Aircraft

BAE Systems (UK), Leonardo (Italy), and Japan Aircraft Industrial Enhancement Co Ltd (JAIEC) have reached an agreement to form a new…

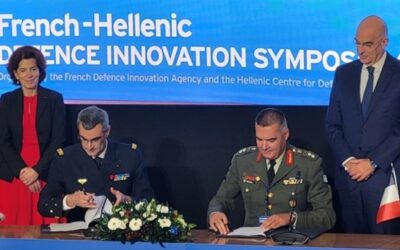

Completion of the French-Hellenic Defence Innovation Symposium

On 12 and 13 December, 2024, the Hellenic Centre of Defence Innovation (HCDI) organised the first French-Hellenic Defence Innovation…

0 Comments